Integrating AI in Sustainable Food and Health Systems: Bridging Nutrigenomics, Clinical Care, and Engineering

| Received 06 Oct, 2025 |

Accepted 20 Jan, 2026 |

Published 21 Jan, 2026 |

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming food systems by offering tools that improve productivity, safety, personalization, and resilience across the value chain. This review synthesizes current evidence on AI applications in agriculture, food processing, personalized nutrition, and supply chain management, and outlines governance and research priorities to ensure that technological gains translate into improved nutrition, equity, and sustainability. This study examined peer-reviewed literature and recent reports to map AI methods, use cases, benefits, and limitations. In agriculture, AI has enhanced precision farming, phenotyping and breeding, and post-harvest handling through sensor-based monitoring, predictive modeling, and automated decision support, leading to improved yields and produce quality. In food safety and processing, computer vision and machine learning have advanced contamination detection, quality grading and process optimization, reducing waste and improving consistency. In personalized nutrition, AI models integrate dietary records, phenotypic indicators and multiomic data to generate individualized recommendations and adaptive interventions that can improve metabolic outcomes and dietary adherence. For supply chain resilience, AI enabled forecasting, traceability and risk assessment support rapid response to disruptions and improve logistical efficiency. Despite demonstrable gains, widespread adoption faces challenges including variable data quality, algorithmic bias, limited transparency, infrastructure gaps, and potential environmental tradeoffs. Equity concerns emerge when resource constrained producers and consumers lack access to data, tools or skills. We propose a framework for responsible AI in food systems that emphasizes standards for data governance and model validation, inclusive design and capacity building, transparent reporting and life cycle assessment to evaluate environmental impacts. Policy levers, public private partnerships and cross disciplinary research are needed to harmonize technological innovation with nutritional and sustainability goals. Finally, we identify priority research areas including scalable validation studies, interoperable data platforms, methods to mitigate bias, and metrics to quantify nutritional and environmental co benefits. By integrating AI with sound governance and evidence based evaluation, the food sector can harness digital advances to support safe, nutritious and sustainable diets at scale. This review offers actionable recommendations for practitioners, researchers and policymakers to guide implementation, monitoring and evaluation of AI interventions that advance food security and public health and equity.

| Copyright © 2026 Anih et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Global food systems are confronting a confluence of challenges rising demand, nutritional inequities, and the imperative to reduce environmental impact, that require integrative technological and policy responses to achieve sustainable, health-promoting diets by 20301. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative enabler across the food value chain, offering scalable tools to monitor safety, enhance productivity, and tailor nutrition strategies to individual and population needs2. In agriculture, AI-driven approaches including precision sensing, predictive modeling, and automated decision support are accelerating breeding, optimizing resource use, and improving the functional properties of produce, thereby strengthening both productivity and nutritional quality3.

Within food industry operations, AI innovations are expanding from quality control and contamination detection to process optimization and product innovation, enabling faster, more reliable manufacturing and responsive product development pipelines4. At the intersection of manufacturing and consumer health, AI supports personalized nutrition by integrating multi-omic data, dietary intake, and lifestyle measures to generate individualized recommendations and adaptive interventions that can improve metabolic outcomes and adherence to healthier diets5. Beyond the farm and factory, the resilience of food supply chains is increasingly bolstered by AI-enabled analytics that enhance demand forecasting, traceability, and organizational responsiveness, helping firms anticipate disruptions and maintain continuity under dynamic conditions6.

Despite its promise, responsible deployment of AI in food and nutrition requires careful attention to data quality, transparency, equity and environmental trade-offs so that technological gains translate into meaningful public-health and sustainability outcomes. This manuscript synthesizes current evidence on AI applications across agriculture, food processing, personalized nutrition and supply-chain resilience, and it outlines a framework for integrating technological innovation with nutritional science and policy to advance sustainable, equitable food systems. The aim is to provide practitioners, researchers, and policymakers with a coherent assessment of where AI is delivering impact today and the priorities for research and governance needed to ensure AI strengthens food security, safety and nutritional well-being at scale.

AI IN NUTRIGENOMICS FOR SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS

AI-driven genomic data analysis for personalized nutrition: The AI-driven analytic frameworks are enabling the interpretation of large-scale genomic datasets to inform personalized dietary recommendations. By integrating SNP profiles, clinical biomarkers, microbiome measures, and lifestyle metadata, modern machine-learning (ML) pipelines detect complex, nonlinear associations between genotype and nutrient metabolism, thereby enabling tailored dietary strategies for disease prevention and health promotion7,8.

In practice, supervised learning models (e.g., random forests, gradient-boosted trees) and ensemble methods are applied to genotype phenotype cohorts to rank polymorphisms by effect size on metabolic endpoints; deep networks and representation learning then extract latent patterns that link variant combinations to nutrient-response phenotypes7,8.

| • | Machine learning for SNP interpretation: The ML approaches improve on classical association testing by capturing epistatic and non-additive effects among SNPs, enabling detection of combinatorial genetic signatures relevant to micronutrient handling and drug nutrient interactions. Models trained on multi-cohort datasets can prioritize SNPs that influence absorption, transport, or enzymatic conversion of vitamins and minerals; these prioritized variants become inputs for downstream predictive rules in clinical decision support7,8 | |

| • | Predictive models for diet gene interactions: Integrative predictive models combine genotype with meal composition and temporal glucose, lipid, or metabolite readouts to forecast individual metabolic responses (e.g., postprandial glycemia, lipid excursion). Such models have shown predictive value for tailoring meal plans, optimizing macronutrient distribution, and informing supplementation strategies that account for genetic predisposition7,8 |

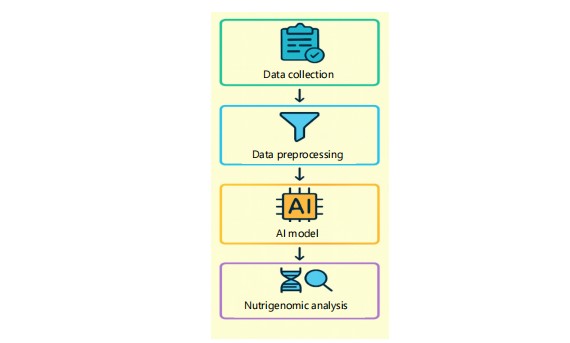

Figure 1 illustrates the sequential stages of the AI-driven nutrigenomic analysis pipeline described. It highlights how raw genomic and lifestyle data are collected, preprocessed, and analyzed through machine learning models. The workflow demonstrates the integration of AI to generate personalized nutrition insights from complex genotype phenotype interactions.

AI in food composition and nutrient profiling: Computer vision and deep learning have matured to the point that automated food recognition and nutrient estimation from images are viable at scale. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), vision transformers, and hybrid ensembles can identify dishes, segment plates, and estimate portion sizes, feeding into nutrient-estimation modules that map visual features to macronutrient and, where available, micronutrient content9,10.

Deep learning for food image recognition and nutrient estimation: Training on large, annotated datasets underpins accurate recognition and portion estimation; transfer learning and multimodal models (image+textual metadata) further improve robustness in real-world settings. The DL-enabled pipelines reduce logging burden for users and clinicians by automating dietary intake capture and generating nutrient summaries suitable for integration with genomic risk scores9,10.

Databases and ontologies for nutrient-gene mapping: The AI-driven nutrigenomics depends on structured knowledge linking food items and nutrient components to gene expression or metabolic pathways. Curated nutrigenomic resources and ontologies standardize descriptors (food taxa, nutrient forms, gene targets), enabling consistent mapping from foods identified by image or self-report to gene-level effects used by predictive models9,10.

|

| Table 1: | Comparative AI tools and databases for nutrient profiling | |||

| Tool/Database | Primary function | Notes/Applications | Citation(s) |

| Food image recognition (DL) |

Identify foods; estimate portion and nutrients |

CNNs/transformer-based systems for automated meal logging |

Liu et al.9 |

| USDA food data Central |

Authoritative nutrient composition |

Core nutrient reference for downstream mapping |

Liu et al.9 and Ford et al.10 |

| FooDB | Food metabolite and bioactive compound database |

Supports nutrient–gene and metabolite pathway mapping |

Liu et al.9 |

| NutrigenomeDB/Eat4Genes | Curated nutrient→gene expression relations |

Databank of experimental nutrigenomic links for models |

Ford et al.10 |

| FoodOn ontology | Standardised food descriptors | Facilitates cross-dataset integration and semantic mapping |

Liu et al.9 and Ford et al.10 |

| Table lists tool/database name, primary function, practical notes and citation to help compare image-recognition and nutrigenomic resources. Entries include deep-learning food-image systems, USDA FoodData Central, FooDB, NutrigenomeDB/Eat4Genes and FoodOn ontology, Abbreviations: AI: Artificial intelligence, DL: Deep learning, CNN: Convolutional neural network, USDA: U.S. Department of Agriculture and DB: Database | |||

Table 1 summarizes core AI tools, image-recognition systems, and curated food/nutrient databases used for automated nutrient profiling and nutrigenomic mapping. It highlights primary functions and practical applications (e.g., portion estimation, ontology mapping) that support image→nutrient pipelines. Use of these resources underpins the section’s discussion of computer-vision and ontology-driven nutrient gene mapping.

AI for crop biofortification and functional food design: The AI accelerates breeding and metabolic design workflows that produce nutrient-dense crops and novel functional foods. The AI-driven genomic selection models and ML-augmented metabolic engineering reduce cycle times and increase the precision of trait introgression, enabling scalable biofortification programs11,12.

| • | Genomic selection in plant breeding: Deep learning models trained on genotype×phenotype panels improve prediction accuracy for complex, quantitative nutrient traits relative to conventional genomic-estimation methods. By more accurately predicting breeding value for micronutrient content, AI enables breeders to select superior parental combinations earlier in breeding cycles, shortening timelines to release biofortified cultivars11,12 | |

| • | AI-assisted metabolic engineering for nutrient-rich crops: Within metabolic engineering, ML tools analyze enzyme kinetics, pathway topology, and gene regulatory networks to nominate edits or transgenes that reroute flux toward desired micronutrients (e.g., provitamin A, folate, iron chelators). AI-guided pathway design reduces experimental iterations, enabling more efficient construction of crops or microbial platforms for functional-ingredient production11,12 |

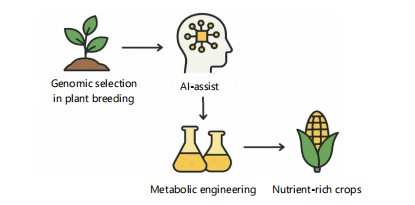

Figure 2 illustrates the AI-assisted biofortification workflow described in of the manuscript, showing how genomic selection feeds into AI-driven analysis that guides metabolic engineering to produce nutrient-rich crops.

It emphasizes the two principal approaches discussed in genomic selection in plant breeding and AI-assisted metabolic engineering and the sequential decisions that shorten breeding cycles and optimize nutrient pathways.

Arrows indicate data and action flow from genotype-informed selection through AI interpretation to laboratory pathway edits and, ultimately, field-ready biofortified cultivars.

Sustainability metrics in AI-driven food systems: The AI applications increasingly connect nutrigenomic and crop-design interventions with environmental assessments, enabling systems-level optimization that balances nutritional goals with planetary constraints13,14.

|

| Table 2: | AI applications for reducing carbon and water footprints | |||

| AI application | Domain | Potential impact/Mechanism | Citation(s) |

| AI-enhanced LCA optimization |

Supply-chain analysis | Identifies supply-chain levers that can reduce GHG emissions (~46%) |

Nikkhah et al.13 |

| Water-footprint prediction (ML) |

Crop water management | High-accuracy water-use estimation enabling targeted conservation |

Nikkhah et al.13 |

| Precision irrigation (AI control) |

Field irrigation | Schedules irrigation using real-time data to reduce water use |

Nikkhah et al.13 and Emeç et al.14 |

| Precision fertilization (ML-guided) |

Nutrient management | Reduces excess fertilizer application and N2O emissions |

Emeç et al.14 |

| Maps AI applications to sustainability domains with short notes on mechanisms and expected impacts. Rows include AI-enhanced LCA optimization, water-footprint prediction, precision irrigation and ML-guided fertilization, Abbreviations: ML: Machine learning, LCA: Life cycle assessment and AI: Artificial intelligence | |||

Life cycle assessment (LCA) integration with AI: Hybrid frameworks that combine LCA inventories with machine-learning optimization enable rapid scenario evaluation and highlight interventions (input substitution, process redesign, logistics optimization) that yield the largest reductions in greenhouse gas emissions or resource use. These hybrid approaches make LCA outputs actionable by automatically recommending operational changes informed by predictive models13,14.

Predictive models for environmental footprint reduction: High-resolution ML models estimate crop water and carbon footprints at farm and regional scales, enabling precision interventions (irrigation scheduling, input matching) that reduce resource consumption without sacrificing yield. Predictive ensembles trained on climatic, soil, and management data have demonstrated high fidelity in water-footprint estimation and provide decision inputs for water- and carbon-saving strategies13,14.

Table 2 maps AI methods to sustainability applications discussed in showing how ML and hybrid LCA approaches reduce environmental impacts. It links specific AI applications (e.g., precision irrigation, LCA optimization) to their domain and expected mechanism of impact. The table supports the section’s argument that AI can make environmental trade-offs actionable.

AI IN CLINICAL CARE FOR NUTRITION AND HEALTH

AI-powered clinical decision support for nutrition therapy: The integration of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) with nutrigenomic data has emerged as a transformative approach in clinical nutrition. By combining genomic profiles with longitudinal health data, AI-driven Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) can generate personalized dietary recommendations that account for genetic predispositions to conditions such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease15.

| Table 3: | AI-enabled clinical nutrition decision support systems | |||

| Component of system | Description | Example applications | Citation(s) |

| Data ingestion layer | Integration of EHR, nutrigenomic, and lifestyle data |

Collects patient history, genetic markers, and dietary logs |

|

| AI analytics engine | Predictive modeling, NLP, reinforcement learning |

Forecasts malnutrition, nutrient deficiencies, and disease risk |

Varayil et al.16 and Bharmal17 |

| Decision support interface | Clinician dashboards and patient-facing apps |

Provides personalized nutrition recommendations |

Bharmal17 |

| Feedback loop | Continuous learning from |

Refines dietary interventions dynamically |

Varayil et al.16 |

| Clinical utility | Reduces clinician workload, improves patient adherence |

Enhances precision nutrition therapy |

Saseedharan and Lewis15 and Varayil et al.16 and Bharmal17 |

| Breaks down system components (data ingestion, analytics engine, interface, feedback loop) with descriptions and example applications. Shows how EHR, nutrigenomic, wearable, and lifestyle inputs feed an AI analytics engine and clinician/patient interfaces, Abbreviations: HER: Electronic health record, CDSS: Clinical decision support system, NLP: Natural language processing and AI: Artificial Intelligence | |||

Machine learning algorithms embedded in EHR platforms can identify nutrient gene interactions, enabling clinicians to tailor interventions at the molecular level16.

Predictive analytics further enhances diet-related disease management by leveraging large-scale datasets to forecast patient outcomes. For example, deep learning models trained on EHR and nutrigenomic data can predict the likelihood of malnutrition, sarcopenia, or micronutrient deficiencies before clinical symptoms manifest17.

These systems also support real-time monitoring of dietary adherence, integrating wearable data streams with clinical records to refine recommendations dynamically.

The architecture of an AI-enabled clinical nutrition decision support system typically includes:

| • | Data ingestion layer: EHR, nutrigenomic, and lifestyle data | |

| • | AI analytics engine: predictive modeling, natural language processing (NLP), and reinforcement learning | |

| • | Decision support interface: clinician dashboards and patient-facing mobile apps | |

| • | Feedback loop: continuous learning from patient outcomes to refine algorithms |

Such systems have demonstrated improved accuracy in predicting diet-related complications, reduced clinician workload, and enhanced patient engagement in nutrition therapy15-17.

Table 3 breaks down components of AI-powered clinical decision support described in (data ingestion, analytics engine, interfaces, feedback loop). It pairs each component with a concise description and example application to show how nutrigenomic data are operationalized in clinical workflows. The Table 3 clarifies the system architecture that underlies clinical personalization claims.

AI in metabolic health monitoring: The rise of wearable sensors and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices has revolutionized metabolic health tracking. The AI algorithms process the vast streams of real-time data from CGMs, accelerometers, and smartwatches to detect subtle physiological changes indicative of metabolic dysregulation18.

For instance, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been applied to CGM data to predict postprandial glucose excursions, enabling proactive dietary adjustments19.

| Table 4: | AI-based metabolic health monitoring devices and algorithms | |||

| Device/Algorithm | Data source | AI technique | Clinical application | Citation(s) |

| Guardian connect (Medtronic) |

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) |

Predictive ML models | Alerts for hypoglycemia/ hyperglycemia |

Choubey et al.18 |

| Dexcom G7 | CGM+cloud integration |

Deep learning forglycemic variability |

Personalized glucose trend prediction |

Anwar et al.19 |

| Smartwatches (Fitbit, apple watch) |

Heart rate, sleep, activity |

Random forest, CNNs | Early detection of metabolic syndrome |

Choubey et al.18 |

| RNN-based CGManalysis | CGM time-series data |

Recurrent neural networks |

Predicts postprandial glucose excursions |

Anwar et al.19 |

| Gradient boosting models |

Multimodal health data | Ensemble learning | Stratifies metabolic syndrome risk |

|

| Catalogs representative devices/algorithms, their data sources and the AI techniques used for metabolic monitoring. Examples include CGM systems (Dexcom/Gardian), smartwatches, RNN-based time-series analyses and ensemble models, Abbreviations: CGM: Continuous glucose monitoring, RNN: Recurrent neural network, CNN: Convolutional neural network and AI: Artificial intelligence | ||||

These models outperform traditional regression-based approaches by capturing nonlinear dynamics in glucose variability.

AI also plays a pivotal role in the early detection of metabolic syndrome (MetS). By integrating multimodal data, such as blood pressure, lipid profiles, and anthropometric measures, machine learning classifiers can identify individuals at high risk of MetS before clinical diagnosis18.

Random forest and gradient boosting models have shown particular promise in stratifying risk across diverse populations.

Table 4 catalogs representative devices and algorithm classes discussed in linking data sources (e.g., CGM, smartwatches) to AI techniques and clinical uses. It provides concrete examples (products and model types) to illustrate the section’s points about real-time metabolic monitoring and prediction. The table supports comparisons of technique, data input, and clinical application.

AI for personalized dietary interventions in chronic disease: The AI-driven personalization of dietary interventions has gained traction in managing chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity20.

Case studies demonstrate that AI-generated diet plans, informed by biomarkers and lifestyle data, can significantly improve glycemic control, lipid profiles, and weight management outcomes21.

For diabetes, reinforcement learning algorithms have been applied to adapt dietary recommendations in real time, adjusting macronutrient composition based on continuous glucose monitoring feedback20,21.

In cardiovascular disease, AI models integrate dietary intake with imaging and biomarker data to optimize heart-healthy diets, such as the DASH or Mediterranean diet21.

Obesity management has benefited from AI-driven behavioral nudges delivered via mobile apps, which personalize caloric targets and meal timing strategies.

The flowchart of AI-driven adaptive dietary intervention typically includes:

| • | Data collection: Biomarkers, wearable data, patient-reported outcomes | |

| • | AI processing: Reinforcement learning and predictive modeling | |

| • | Personalized intervention: Adaptive meal plans and behavioral prompts | |

| • | Outcome monitoring: Continuous feedback loop for refinement |

| Table 5: | AI-driven personalized dietary interventions in chronic disease | |||

| Chronic disease | AI approach | Intervention strategy | Clinical outcome | Citation(s) |

| Diabetes | Reinforcement learning with CGM feedback |

Adaptive macronutrient adjustments |

Improved glycemic control |

Wang et al.20 |

| Cardiovascular disease | Predictive modeling with biomarkers and imaging |

Optimized DASH/ Mediterranean diet plans |

Reduced CVD risk markers |

Wang et al.20 |

| Obesity | AI-driven behavioral nudges via mobile apps |

Personalized caloric targets and meal timing |

Enhanced weight loss adherence |

Wang et al.20 |

| Multi-disease management |

Hybrid AI models integrating lifestyle+ biomarkers |

Adaptive diet plans across comorbidities |

Improved long-term adherence |

Gavai and van Hillegersberg21 |

| Patient engagement | Conversational AI and mobile coaching |

Real-time feedback and motivation |

Higher adherence rates |

Gavai and van Hillegersberg21 |

| Pairs chronic conditions with AI approaches, intervention strategies and reported clinical outcomes. Rows include diabetes (reinforcement-learning with CGM feedback), CVD (predictive modeling+biomarkers) and obesity (behavioral nudges via apps), Abbreviations: RL: Reinforcement learning, CVD: Cardiovascular disease, CGM: Continuous glucose monitoring and AI: Artificial intelligence | ||||

These adaptive systems have demonstrated superior adherence rates compared to static diet plans, highlighting the potential of AI to transform chronic disease management20,21.

Table 5 summarizes AI approaches for chronic-disease dietary management covered in pairing diseases (diabetes, CVD, obesity) with algorithmic strategies and measured outcomes. It clarifies which AI methods (e.g., reinforcement learning, predictive modeling) map to which intervention strategies and clinical endpoints. The table condenses case-study evidence supporting adaptive, AI-tailored diets.

AI in public health nutrition surveillance: At the population level, AI has become indispensable in nutrition surveillance. Machine learning models analyze dietary intake data from national surveys, retail purchase records, and social media to identify emerging dietary patterns22.

For example, natural language processing applied to food diaries and online discussions can reveal shifts in consumption trends, such as increased plant-based diets or ultra-processed food intake23.

Predictive modeling has also been employed to forecast malnutrition and obesity trends. By integrating socioeconomic, environmental, and dietary data, AI systems can predict hotspots of undernutrition or obesity, guiding targeted public health interventions24.

These models have been used to simulate the impact of policy measures, such as sugar taxes or food subsidy programs, on population dietary behaviors.

Table 6 lists model classes and primary data sources used for population-level nutrition surveillance as discussed in alongside intended public-health impacts. It showcases how NLP, deep learning, Bayesian networks and random-forest models are applied to surveys, satellite imagery and social media. The table highlights surveillance use-cases and the policy-relevant outputs each model class can generate.

ENGINEERING INNOVATIONS FOR AI-ENABLED FOOD AND HEALTH SYSTEMS

Smart food production systems: The integration of IoT-enabled precision agriculture with AI has transformed farming into a data-driven enterprise. Smart sensors now monitor soil moisture, nutrient levels, and microclimatic conditions in real time, enabling farmers to optimize irrigation, fertilization, and pest control strategies25.

The AI algorithms process these heterogeneous data streams to generate predictive models that guide planting schedules, crop rotation, and yield forecasting26.

| Table 6: | AI models in public health nutrition surveillance | |||

| AI model | Data source | Application | Public health impact | Citation(s) |

| Random forest models | National dietary surveys | Predict obesity prevalence | Guides obesity prevention programs |

An and Wang22 |

| Deep learning models | Satellite imagery of food environments |

Identifies food deserts and obesogenic areas |

Supports urban planning and food policy |

Ferreira et al.23 |

| Bayesian networks | Socioeconomic+dietary data |

Forecasts malnutrition risk | Targets vulnerablepopulations | |

| NLP-based models | Food diaries, social media | Detects emerging dietary trends |

Monitors shifts in population diet |

Ferreira et al.23 and Mendes et al.24 |

| Predictive policy simulations |

Integrated socioeconomic+ nutrition datasets |

Models impact of sugar taxes, subsidies |

Informs national nutrition policy |

Mendes et al.24 |

| Lists AI model classes, primary data sources, applications and the public-health impacts they generate. Includes random-forest models on national surveys, deep learning on satellite imagery, Bayesian networks on socioeconomic+diet data, and NLP on diaries/social media, Abbreviations: RF: Random forest, DL: Deep learning, BN: Bayesian network, NLP: Natural language processing and ML: Machine learning | ||||

| Table 7: | Smart food production systems | |||

| Technology | Application | Benefits | Citation(s) |

| IoT soil sensors | Monitor soil moisture, nutrients |

Precision irrigation and fertilization | Miller et al.25 |

| AI crop models | Predict yield, detect stress | Optimized planting and harvesting | Miller et al.25 and Chaurasiya et al.26 |

| Vertical farming AI | Climate and nutrient control | Year-round production, reduced water use | Chaurasiya et al.26 |

| Robotics in farming | Automated seeding, harvesting |

Reduced labor costs, higher efficiency | |

| Cloud-based platforms | Remote monitoring and analytics |

Scalable smart farm management | Oh and Lu27 |

| Itemizes smart-farm technologies, their specific applications and the main productivity/sustainability benefits. Entries include IoT soil sensors, AI crop models, vertical/controlled-environment farming systems, robotics and cloud platforms, Abbreviations: IoT: Internet of things, AI: Artificial Intelligence; CEA: Controlled-environment agriculture and SW/HW: Software/hardware (where applicable) | |||

Vertical farming and controlled environment agriculture (CEA) represent another frontier. By leveraging AI-driven climate control systems, vertical farms can regulate light spectra, CO2 concentration, and nutrient delivery to maximize crop productivity27.

These systems reduce water consumption by up to 90% compared to traditional agriculture, while minimizing pesticide use and ensuring year-round production.

The smart farm architecture integrates IoT sensors, robotics, and AI analytics into a closed-loop system:

| • | IoT sensors capture soil, plant, and environmental data | |

| • | The AI analytics optimize resource allocation and predict crop stress | |

| • | Robotics automate seeding, harvesting, and crop monitoring | |

| • | Cloud platforms enable remote decision-making and scalability |

This convergence enhances sustainability, reduces labor dependency, and improves resilience against climate variability25-27.

Table 7 itemizes smart-farm technologies described in matching each technology (IoT soil sensors, AI crop models, vertical-farm AI, robotics, cloud platforms) with applications and primary benefits. It provides a quick reference that connects specific engineering tools to sustainability and productivity outcomes. The table supports the section’s claims about closed-loop farm optimization.

| Table 8: | AI applications in food safety and quality control | |||

| AI Application | Technology | Use case | Benefits | Citation(s) |

| Contamination detection |

Computer vision+ CNNs |

Identify microbial/foreign objects |

Real-time safety assurance |

Dhal and Kar28 |

| Shelf-life prediction | Machine learning regression |

Predict spoilage timelines |

Reduced food waste | Dhal and Kar28 |

| Predictive maintenance | Sensor data+ML models |

Anticipate equipment failure |

Reduced downtime, safer production |

|

| Automated quality control |

Vision+NLP | Detect texture, color, defects | Consistency in food quality |

Song et al.29 |

| Risk modeling | AI+IoT integration | Hazard analysis | Proactive safety management |

Song et al.29 |

| Summarizes AI use-cases in processing and safety, listing technologies, use-cases and operational benefits (e.g., real-time contamination detection, shelf-life prediction). Rows cover computer-vision contamination detection, ML shelf-life regression, predictive maintenance from sensor data and automated quality control, Abbreviations: CNN: Convolutional neural network, ML: Machine learning, IoT: Internet of Things, AI: Artificial intelligence and NLP: Natural language processing | ||||

AI in food processing and safety engineering: Food safety remains a global challenge, with contamination incidents causing significant health and economic burdens. Computer vision systems powered by deep learning are increasingly deployed in food processing plants to detect microbial contamination, foreign objects, and quality defects28.

These systems outperform manual inspection by providing real-time, high-resolution analysis of food products on production lines.

Predictive maintenance is another critical application. The AI models analyze sensor data from machinery, such as vibration, temperature, and acoustic signals, to predict equipment failures before they occur29.

This reduces downtime, prevents contamination risks from malfunctioning equipment, and lowers operational costs.

Together, these innovations enhance food safety, improve quality assurance, and strengthen consumer trust28,29.

Table 8 summarizes AI use-cases in processing and safety discussed in pairing each AI application (contamination detection, shelf-life prediction, predictive maintenance) with the enabling technology and the operational benefit. It clarifies how real-time vision and sensor analytics reduce risks and downtime. The table acts as a concise inventory for food-safety engineering interventions.

AI-driven supply chain optimization for sustainable food distribution: The food supply chain faces challenges of demand variability, waste, and traceability. AI-driven demand forecasting models use historical sales, weather data, and consumer behavior to predict demand with high accuracy30.

This reduces overproduction, minimizes waste, and ensures timely distribution.

Blockchain integration enhances traceability by creating immutable records of food movement across the supply chain31.

When combined with AI, blockchain enables real-time fraud detection, contamination source tracing, and compliance monitoring32.

| Table 9: | AI in sustainable food supply chain optimization | |||

| Application | AI/Tech used | Benefits | Citation(s) |

| Demand forecasting | ML, deep learning | Reduced waste, accurate planning | Chen et al.30 |

| Route optimization | AI logistics models | Lower emissions, faster delivery | Chen et al.30 |

| Blockchain traceability | Blockchain+AI | Fraud prevention, transparency | Zhu et al.31 |

| Inventory optimization | Predictive analytics | Reduced spoilage, cost savings | Qian et al.32 |

| Sustainability tracking | AI+IoT | Carbon footprint monitoring | Qian et al.32 |

| Lists supply-chain applications (demand forecasting, route optimization, blockchain traceability, inventory and sustainability tracking) with AI/tech and benefits. Shows how ML/AI forecasts and blockchain-ledgers combine with IoT to reduce waste, lower emissions and improve traceability, Abbreviations: ML: Machine learning, AI: Artificial intelligence, IoT: Internet of things and BC: Blockchain | |||

The AI-enabled sustainable food supply chain model includes:

| • | Data collection: IoT sensors, retail data, logistics | |

| • | The AI forecasting: Demand prediction, route optimization | |

| • | Blockchain ledger: Transparent traceability | |

| • | Sustainability metrics: Carbon footprint, waste reduction |

This integration improves efficiency, reduces environmental impact, and strengthens consumer confidence30-32.

Table 9 lists supply-chain applications (demand forecasting, route optimization, blockchain traceability, inventory optimization, sustainability tracking) discussed and the AI/tech used for each. It links each application to its operational benefit (waste reduction, lower emissions, fraud prevention). The table synthesizes the section’s proposed model for AI+blockchain-enabled sustainable distribution.

Human-AI collaboration in food and health engineering: The success of AI in food and health systems depends on human AI collaboration. The Co-design approaches involving nutritionists, clinicians, and engineers ensure that AI tools are user-centered, clinically relevant, and ethically aligned33.

Collaborative design workshops have shown that involving domain experts improves algorithm interpretability and adoption.

Ethical and regulatory considerations are equally critical. Issues such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and accountability must be addressed to ensure trust in AI systems34.

Regulatory frameworks are emerging to guide responsible AI deployment in food and health engineering, emphasizing transparency, fairness, and human oversight35.

This collaboration ensures that AI augments rather than replaces human expertise, fostering innovation while safeguarding ethical standards33-35.

Table 10 maps ethical principles (transparency, fairness, accountability, privacy, human-centric design) described in to concrete frameworks/guidelines and their application in food-health AI systems. It clarifies governance levers and recommended practices for trustworthy deployment. The table supports the section’s emphasis on co-design and regulatory alignment.

RECOMMENDATION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Artificial intelligence holds real promise for nutrigenomics, food engineering and clinical nutrition, but realizing that promise requires practical, people centered action. We recommend three mutually reinforcing priorities. First, strengthen data governance and adopt open, interoperable ontologies so that datasets can be combined responsibly and traced back to their origin. Second, commit to prospective, multi site model validation using diverse cohorts and realistic field data to make sure tools work beyond the lab. Third, embed human centered design from the start so that equity, explainability and usability guide both research and deployment. These foundational steps will reduce bias, build clinician and public trust, and accelerate safe translation into practice36-38.

| Table 10: | Ethical frameworks and guidelines for ai in food-health systems | |||

| Ethical principle | Framework/Guideline | Application in food-Health AI | Citation(s) |

| Transparency | EU AI Act, FDA guidelines | Explainable AI in nutrition tools | Jumper et al.33 |

| Fairness | IEEE Ethically Aligned Design | Avoid bias in dietary algorithms | Payili34 |

| Accountability | WHO digital health ethics | Human oversight in AI decisions | Agrawal et al.35 |

| Privacy and security | GDPR, HIPAA | Protect patient and consumer data | |

| Human-centric design | Co-design methodologies | Collaboration with clinicians/nutritionists | Agrawal et al.35 |

| Maps ethical principles to concrete frameworks/guidelines and their application in food-health AI deployments. Entries include transparency (EU AI Act/FDA guidance), fairness (IEEE EAD), accountability (WHO digital health ethics), and privacy (GDPR/HIPAA), Abbreviations: EU AI Act: European union AI act, FDA: U.S. Food and drug administration, WHO: World health organization, GDPR: General data protection regulation, HIPAA: Health insurance portability and accountability Act, IEEE EAD: IEEE ethically aligned design and AI: Artificial intelligence | |||

On the research and engineering side, we urge focused investment in longitudinal, multi cohort clinical studies that connect genomic, microbiome, clinical and behavior data to clear health outcomes. Build modular, interoperable platforms that enable federated learning and privacy preserving analytics so institutions can collaborate without exposing sensitive data. Pair AI model development with life cycle assessment and supply chain impact evaluation so nutritional gains do not come at the expense of planetary health. Equip biochemists, nutritionists and engineers with applied AI literacy and support cross discipline teams that can translate algorithmic insights into safe laboratory and clinical practice. These measures reflect and extend recent work on integrating AI into biomolecular research39.

Practical implementation also needs supportive policy, funding and governance. Funders should create targeted streams for implementation research in low resource settings and for independent validation studies. Regulators, industry and civil society should require transparent model documentation, versioned audit trails and accessible model cards so decisions informed by AI are auditable and explainable. Convene multi stakeholder governance fora that include researchers, clinicians, community representatives and industry to steward deployment and to align incentives with public health and sustainability39.

Finally, promote open science as the default. Shared, well curated datasets and reproducible pipelines accelerate progress and reduce duplication. Incentivize reproducible code release, curated benchmark datasets and registered reports so that findings are verifiable and translatable. Encourage partnerships that pair technological innovation with implementation science so that promising tools mature into usable, safe interventions. These recommendations align with recent analyses on AI integration in biochemistry and biomedical sciences39,40. By centering ethics, transparency and collaboration we can move from individual proofs of concept to durable improvements in nutrition and health39,40.

CONCLUSION

Based on the integrated review and analyses presented in this manuscript, AI-enabled nutrigenomics and engineering innovations demonstrate strong potential to personalize nutrition and advance sustainable food systems. Machine-learning frameworks for genomic interpretation, computer-vision nutrient profiling, and AI-assisted biofortification collectively offer scalable routes to improve nutrient outcomes while lowering environmental footprints. Clinical deployment of AI-via EHR-integrated decision support, CGM-informed adaptive diets, and wearable-enabled monitoring can enhance prevention and management of diet-related disease when validated in diverse populations. Engineering advances (IoT-driven precision agriculture, vertical farming, and AI-optimized logistics with blockchain traceability) provide actionable mechanisms to reduce waste, water use, and emissions across supply chains. Robust validation, data interoperability, and transparent governance are prerequisites for safe, equitable adoption; attention to algorithmic bias, privacy and regulatory compliance must guide implementation. Overall, the manuscript outlines a pragmatic agenda that balances technological innovation with ethical, regulatory and socioecological safeguards to realize AI-driven nutrition and food systems at scale.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This manuscript synthesizes advances in AI applications across nutrigenomics, crop biofortification, food processing, supply chain engineering and clinical nutrition, highlighting integrated pathways to improve nutrition and sustainability. It shows how machine learning, computer vision and metabolic engineering can accelerate development of nutrient rich crops and enable precision dietary interventions. The review underscores systems level integration with life cycle assessment and supply chain analytics to align nutritional objectives with environmental constraints. Ethical governance, data interoperability and rigorous validation are identified as prerequisites for equitable, safe and transparent deployment. Priority future actions include longitudinal multi cohort studies, standardized ontologies and open data practices to strengthen model generalizability and reproducibility. By combining technical, policy and codesign perspectives, the manuscript offers a pragmatic roadmap for translating AI enabled innovations into scalable, equitable food and health solutions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge the colleagues and librarians who assisted with literature searches, source identification, and critical readings that substantially improved this review. This manuscript is a synthesis of published studies and secondary sources; we thank the original authors whose work formed the basis of our analysis. We also acknowledge institutional support and constructive feedback from peer reviewers and colleagues that strengthened the review’s clarity and scope.

REFERENCES

- Varzakas, T. and S. Smaoui, 2024. Global food security and sustainability issues: The road to 2030 from nutrition and sustainable healthy diets to food systems change. Foods, 13.

- Liu, Z., S. Wang, Y. Zhang, Y. Feng, J. Liu and H. Zhu, 2023. Artificial intelligence in food safety: A decade review and bibliometric analysis. Foods, 12.

- Nautiyal, M., S. Joshi, I. Hussain, H. Rawat and A. Joshi et al., 2025. Revolutionizing agriculture: A comprehensive review on artificial intelligence applications in enhancing properties of agricultural produce. Food Chem.: X, 29.

- Yang, H., W. Jiao, L. Zouyi, H. Diao and S. Xia, 2025. Artificial intelligence in the food industry: Innovations and applications. Discover Artif. Intell., 5.

- Agrawal, K., P. Goktas, N. Kumar and M.F. Leung, 2025. Artificial intelligence in personalized nutrition and food manufacturing: A comprehensive review of methods, applications, and future directions. Front. Nutr., 12.

- Guo, X., Y. Chen, J. Xie, H. Wang and X. Lei, 2025. Research on supply chain resilience mechanism of AI-enabled manufacturing enterprises -based on organizational change perspective. Sci. Rep., 15.

- Papastratis, I., D. Konstantinidis, P. Daras and K. Dimitropoulos, 2024. AI nutrition recommendation using a deep generative model and ChatGPT. Sci. Rep., 14.

- Kan, J., J. Ni, K. Xue, F. Wang and J. Zheng et al., 2022. Personalized nutrition intervention improves health status in overweight/obese Chinese adults: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Nutr., 9.

- Liu, D., E. Zuo, D. Wang, L. He, L. Dong and X. Lu, 2025. Deep learning in food image recognition: A comprehensive review. Appl. Sci., 15.

- Ford, M.L., J.M. Cooley, V. Sripada, Z. Xu, J.S. Erickson, K.P. Bennett and D.R. Crawford, 2023. Eat4Genes: A bioinformatic rational gene targeting app and prototype model for improving human health. Front. Nutr., 10.

- Wang, H., S. Yan, W. Wang, Y. Chen and J. Hong et al., 2025. Cropformer: An interpretable deep learning framework for crop genomic prediction. Plant Commun., 6.

- Merzbacher, C. and D.A. Oyarzún, 2023. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in dynamic pathway engineering. Biochem. Soc. Trans., 51: 1871-1879.

- Nikkhah, A., M. Esmaeilpour, A. Kosari‐Moghaddam, A. Rohani and F. Nikkhah et al., 2024. Machine learning-based life cycle assessment for environmental sustainability optimization of a food supply chain. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manage., 20: 1759-1769.

- Emeç, M., A. Muratoğlu and M.S. Demir, 2025. High-resolution global modeling of wheat’s water footprint using a machine learning ensemble approach. Ecol. Processes, 14.

- Saseedharan, S. and H. Lewis, 2024. The application of AI in clinical nutrition. Int. J. Nutr. Res. Health, 3.

- Varayil, J.E., S.J. Bielinski, M.S. Mundi, S.L. Bonnes, B.R. Salonen and R.T. Hurt, 2025. Artificial intelligence in clinical nutrition: Bridging data analytics and nutritional care. Curr. Nutr. Rep., 14.

- Bharmal, A.R., 2025. Transforming healthcare delivery: AI-powered clinical decision support systems. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol., 11: 339-347.

- Choubey, U., V.A. Upadrasta, I.P. Kaur, H. Banker and S.G. Kanagala et al., 2024. From prevention to management: Exploring AI’s role in metabolic syndrome management: A comprehensive review. Egypt. J. Intern. Med., 36.

- Anwar, A., S. Rana and P. Pathak, 2025. Artificial intelligence in the management of metabolic disorders: A comprehensive review. J. Endocrinol. Invest., 48: 1525-1538.

- Wang, X., Z. Sun, H. Xue and R. An, 2025. Artificial intelligence applications to personalized dietary recommendations: A systematic review. Healthcare, 13.

- Gavai, A.K. and J. van Hillegersberg, 2025. AI-driven personalized nutrition: RAG-based digital health solution for obesity and type 2 diabetes. PLOS Digital Health, 4.

- An, R. and X. Wang, 2023. Artificial intelligence applications to public health nutrition. Nutrients, 15.

- Ferreira, D.D., L.G. Ferreira, K.A. Amorim, D.C.T. Delfino, A.C.B.H. Ferreira and L.P.Castro e Souza, 2025. Assessing the links between artificial intelligence and precision nutrition. Curr. Nutr. Rep., 14.

- Mendes, V.I.S., B.M.F. Mendes, R.P. Moura, I.M. Lourenço, M.F.A. Oliveira, K.L. Ng and C.S. Pinto, 2025. Harnessing artificial intelligence for enhanced public health surveillance: A narrative review. Front. Public Health, 13.

- Miller, T., G. Mikiciuk, I. Durlik, M. Mikiciuk, A. Łobodzińska and M. Śnieg, 2025. The IoT and AI in agriculture: The time is now-a systematic review of smart sensing technologies. Sensors, 25.

- Chaurasiya, P., S. Kumar, V.K. Patel and O.C. Pandey, 2025. Revolutionizing crop production: AI-driven precision agriculture, vertical farming, and sustainable resource optimization. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res., 9: 506-519.

- Oh, S. and C. Lu, 2023. Vertical farming-smart urban agriculture for enhancing resilience and sustainability in food security. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol., 98: 133-140.

- Dhal, S.B. and D. Kar, 2025. Leveraging artificial intelligence and advanced food processing techniques for enhanced food safety, quality, and security: A comprehensive review. Discover Appl. Sci., 7.

- Song, X., X. Zhang, G. Dong, H. Ding and X. Cui et al., 2025. AI in food industry automation: Applications and challenges. Front. Sustainable Food Syst., 9.

- Chen, W., Y. Men, N. Fuster, C. Osorio and A.A. Juan, 2024. Artificial intelligence in logistics optimization with sustainable criteria: A review. Sustainability, 16.

- Zhu, L., P. Spachos, E. Pensini and K.N. Plataniotis, 2021. Deep learning and machine vision for food processing: A survey. Curr. Res. Food Sci., 4: 233-249.

- Qian, C., S.I. Murphy, R.H. Orsi and M. Wiedmann, 2023. How can AI help improve food safety? Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol., 14: 517-538.

- Jumper, J., R. Evans, A. Pritzel, T. Green and M. Figurnov et al., 2021. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596: 583-589.

- Payili, P., 2025. Human-AI collaboration in food delivery. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol., 11: 45-52.

- Agrawal, K., P. Goktas, M. Holtkemper, C. Beecks and N. Kumar, 2025. AI-driven transformation in food manufacturing: A pathway to sustainable efficiency and quality assurance. Front. Nutr., 12.

- Detopoulou, P., G. Voulgaridou, P. Moschos, D. Levidi and T. Anastasiou et al., 2023. Artificial intelligence, nutrition, and ethical issues: A mini-review. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci., 50: 46-56.

- Naseem, S. and M. Rizwan, 2025. The role of artificial intelligence in advancing food safety: A strategic path to zero contamination. Food Control, 175.

- Abrahams, M. and M. Raimundo, 2025. Perspective on the ethics of AI at the intersection of nutrition and behaviour change. Front. Aging, 6.

- Anih, D.C., K.A. Arowora, M.A. Abah, K.C. Ugwuoke and B. Habibu, 2025. Redefining biomolecular frontiers: The impact of artificial intelligence in biochemistry and medicine. J. Med. Sci., 25: 1-10.

- Arowora, A.K., I. Chinedu, D.C. Anih, A.A. Moses and K.C. Ugwuoke, 2022. Application of artificial intelligence in biochemistry and biomedical sciences: A review. Asian Res. J. Curr. Sci., 4: 302-312

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Anih,

D.C., Okorocha,

U.C., Attahiru,

U., Tayo-Ladega,

O., Ahmed,

A.A., Omokaro,

L., kurna,

A.A., Olaitan,

S.L., Linus,

E.N. (2026). Integrating AI in Sustainable Food and Health Systems: Bridging Nutrigenomics, Clinical Care, and Engineering. Science International, 14(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.17311/sciintl.2026.01.15

ACS Style

Anih,

D.C.; Okorocha,

U.C.; Attahiru,

U.; Tayo-Ladega,

O.; Ahmed,

A.A.; Omokaro,

L.; kurna,

A.A.; Olaitan,

S.L.; Linus,

E.N. Integrating AI in Sustainable Food and Health Systems: Bridging Nutrigenomics, Clinical Care, and Engineering. Sci. Int 2026, 14, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.17311/sciintl.2026.01.15

AMA Style

Anih

DC, Okorocha

UC, Attahiru

U, Tayo-Ladega

O, Ahmed

AA, Omokaro

L, kurna

AA, Olaitan

SL, Linus

EN. Integrating AI in Sustainable Food and Health Systems: Bridging Nutrigenomics, Clinical Care, and Engineering. Science International. 2026; 14(1): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.17311/sciintl.2026.01.15

Chicago/Turabian Style

Anih, David, Chinonso, Ugochukwu Cyrilgentle Okorocha, Ummulkulsum Attahiru, Oluwadamisi Tayo-Ladega, Ahmed Abdullahi Ahmed, Loveth Omokaro, Abatcha Alhaji kurna, Sulaiman Luqman Olaitan, and Emmanuel Ndirmbula Linus.

2026. "Integrating AI in Sustainable Food and Health Systems: Bridging Nutrigenomics, Clinical Care, and Engineering" Science International 14, no. 1: 1-15. https://doi.org/10.17311/sciintl.2026.01.15

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.